Published in the SF Bayview, February 26, 2018

by Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa and Baridi J. Williamson

California Department of Corrections and rehabilitation (CDCr) had been locking classes of prisoners up in solitary confinement since the ‘60s as part of CDCr’s para-military low-intensity warfare, to break the minds and spirits of its subjects, California’s prisoner class. CDCr’s solitary confinement has two operating components: 1) punishing you and 2) physically and mentally destroying you.

In the 1970s, CDCr’s report to then Gov. Ronald Reagan on revolutionary organizations and gangs resulted in Reagan ordering the CDCr director to lock up all radicals, militants, revolutionaries and jailhouse lawyers who were considered “trouble-makers.”[i] And a 1986 report by the CDCr task force stated that during the ‘60s and ‘70s, California’s prisoners became “politicized” through the influence of outside “radical, social movements.”

And conscious prisoners began to “demand” their human, constitutional and civil rights,[ii] as exemplified by those politicized prisoners of war (PPOW) like W.L. Nolen.[iii] In the late ‘60s, Nolen and other PPOWs filed a civil rights class action case challenging the inhumane, degrading conditions and institutional racism that was prevalent at Soledad Prison’s solitary confinement O-wing,[iv] as well as throughout CDCr’s prison system to date.

The 1986 CDCr task force report recommended that CDCr build “supermax” prisons for this politicized class of prisoners, which was echoed by the California prison guards’ union (known today as CCPOA) in continuing their low-intensity warfare upon California prisoners up into and through the ‘80s.

Shortly thereafter, California government through its apparatus CDCr, built its solitary confinement torture sites, such as Security Housing Units (SHUs) and Administrative Segregation (Ad-Segs) at Tehachapi in December 1986, New Folsom in December 1987, Corcoran in December 1988 and at Pelican Bay State Prison in December of 1989. All were designed with the malicious intent to destroy human lives through their diabolical low-intensity warfare scheme of mass validation – group punishment – indeterminate SHU classification and enhanced “debriefing” interrogation, known as “snitch, parole or die!”

Each of California’s governors and CDCr cabinet secretaries from 1977 to 2015 knowingly enhanced their system to become more repressive upon the prisoners held in solitary confinement in the SHUs. We prisoners have known for the past decades that California citizens have not condoned the torture of California prisoners. Nevertheless, since the ‘60s, each state governor and legislature knowingly sanctioned solitary confinement torture.

California’s CDCr – with the winks and nods of lawmakers and judges – has held countless prisoners in solitary confinement, whether it is called Ad-Seg, Management Control Unit, Adjustment Center, SHU or Administrative SHU, longer than any prison system within the United States, ranging up to 45 years of torture and acts of racial discrimination from Soledad Prison’s O-wing to PBSP’s new form of solitary confinement torture.

The case of Madrid v. Gomez was the first acknowledgement on the part of California authorities and judiciary recognizing the harm that CDCr had been causing – mental torture – to those held in solitary confinement across the state’s prison system.[v]

We prisoners have known for the past decades that California citizens have not condoned the torture of California prisoners. Nevertheless, since the ‘60s, each state governor and legislature knowingly sanctioned solitary confinement torture.

The Madrid case touched on the harsh conditions and treatment toward the solitary confinement prisoners at PBSP. It is a clear fact that during the years 1989 to 1994, PBSP had one of the most notorious Violence Control Units (VCUs) in the U.S. CDCr-PBSP officials utilized the VCU for to violate prisoners’ human, constitutional and civil rights by beating us and destroying the minds and spirits of so many of us for years.

An example of how some prisoners would find themselves forced into PBSP’s VCU is when the CDCr bus would arrive at PBSP and park outside the entrance doorway to solitary confinement – Facilities C and D. A squad of goons dressed in paramilitary gear with black gloves, shields and riot helmets would be there waiting. They called themselves the “Welcoming Committee.”

These guards, describing themselves as the Green Wall guard gang, using “G/W” and “7/23” as symbols for “Green Wall,” would roam through the SHU corridors assaulting, beating and scalding prisoners. See Madrid v. Gomez.

The Welcoming Committee would select one or more prisoners and pull them off the bus – usually choosing those the transportation guards accused of “talking loud.” They would take each one to the side and jump on him, then drag him off through the brightly lighted doorway.

These guards, describing themselves as the Green Wall guard gang, using “G/W” and “7/23” as symbols for “Green Wall,” would roam through the SHU corridors assaulting, beating and scalding prisoners.

When the rest of the prisoners were escorted off the bus into the corridor to be warehoused in the general SHU cells, they would see those beaten prisoners dragged off the bus “hog-tied”[vi] and lying on their stomachs or crouched in a fetal position, sometimes in a pool of blood.[vii]Later, they were dragged off to the VCU, where they were targeted with intense mind-breaking operations.

When these prisoners were eventually taken out of VCU and housed in the general SHU cells, they mostly displayed insanity – smearing feces all over their bodies, screaming, yelling, banging cups, throwing urine.[viii] And it was only when prisoners began to go public about the VCU at PBSP that CDCr ceased those practices.[ix]

The effects of solitary confinement at PBSP compelled CDCr to establish Psychiatric Service Units (PSUs) in response to the Madrid ruling for remedying the conditions that were destroying the minds of all prisoners who were held captive from the time of the Madrid ruling in 1995 through 2014, but they were poor and ineffective. Those released to the PSU from SHU fared no better than others held in solitary confinement at PBSP.

Prisoners in SHU continued to suffer mental, emotional and physical harm with no remedy made available by CDCr until we were released out to General Population units by the Departmental Review Board (DRB) between 2012 and 2014 and the Ashker v. Brown class action settlement in 2015.

These released prisoners were coming from a torture chamber, where by necessity they created coping skills like self-medicating. Typically, when coming out of solitary confinement, women and men prisoners show signs of depressive disorder and symptoms characteristic of self-mutilation, mood deterioration and depression, traumatic stress disorder, hopelessness, panic disorder, anger, obsessive-compulsive disorder, irritability, anhedonia, fatigue, feelings of guilt, loss of appetite, nervousness, insomnia, worry, increased heart rate and respiration, sweating, hyperarousal, serious problems with socialization, paranoia, loss of appetite, as well as cognitive issues, nightmares, muscle tension, intrusive thoughts, fear of losing control, and difficulty concentrating.[x]

Prisoners in SHU continued to suffer mental, emotional and physical harm with no remedy made available by CDCr until we were released out to General Population units by the Departmental Review Board (DRB) between 2012 and 2014 and the Ashker v. Brown class action settlement in 2015.

The California prison system realized that these prisoners held initially at PBSP and subsequently at Tehachapi and throughout the system had their constitutional rights violated under the Eighth Amendment ban against cruel and unusual punishment and the 14th Amendment guarantee of due process of the law, for decades.[xi]

Jules Lobel of the Center for Constitutional Rights and lead counsel in Ashker stated:

“The torture of solitary confinement doesn’t end when the cell doors open. California’s continued violation of the Constitution and new evidence of the persistent impact of prolonged solitary confinement requires CDCR to make essential changes in their conduct and rehabilitative programs, and, more broadly, demonstrates the urgent need to end solitary confinement across the country.”[xii]

The Ashker v. Brown class action, settled in 2015, is a historic lawsuit exposing those violations and the harms they cause. We, as California prisoners and citizens of this state, deserve to be treated for the intentional cruelty caused by state-sanctioned torture. This is especially so for the hundreds of solitary confinement prisoners who have spent more than 27 months in any form of solitary confinement, which constitutes torture, according to the Ninth Circuit.[xiii]

CDCr has continued to shun its governmental responsibilities and has not effectively remedied the pain and suffering of thousands of solitary confinement prisoners who have been released to General Population through the DRB and Ashker. All of them are suffering from various aspects of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Solitary Confinement (PTSDSC).

We, as California prisoners and citizens of this state, deserve to be treated for the intentional cruelty caused by state-sanctioned torture.

If you are reading this, join us in writing, emailing and calling Gov. Brown (916-445-2841 or jerry.brown@gov.ca), Secretary of CDCr Scott Kernan (916-324-7308) and Sen. Holly Mitchell (916-324-7308 or http://sd30.senate.ca.gov/e-mail-holly), who chairs the Public Safety Committee overseeing CDCr, and demand the following government actions be taken to remedy the decades of damage done to us:

- That CDCr provide statewide men’s and women’s PTSDSC support groups modeled after the “Men’s’ Group” program we created at Salinas Valley State Prison Facility C, which has been approved by the administration – wardens, community resources managers (CRMs) – for our PTSDSC class and is only awaiting locating a sponsor to get started;

- That CDCr allow all PTSDSC prisoners to go through this six-month relief program at their respective GP locations;

- That CDCr provide effective in-service training of staff in fairly and respectfully dealing with PTSDSC class members, including in appeals, disciplinary and medical matters;

- That CDCr adopt all recommendations in the 2017 report of the Human Rights in Trauma Mental Health Lab at Stanford University, detailing the ongoing negative health consequences that Ashker class members have suffered following their release from long-term solitary confinement into GP:

- Provide peer-facilitated support groups for all PTSDSC class members; and

- Provide independent psychiatric care for all PTSDSC class members to receive PTSDSC mental and emotional health and psychological services in this form.

- That Gov. Brown and the California legislature order the Board of Parole Hearings to stop denying our PTSDSC class members who are serving life sentences a fair opportunity to be released home, thereby doubly punishing and torturing us because we were unlawfully kept in solitary confinement without due process and exercised our constitutionally protected right to peacefully protest with hunger strikes to be released, refusing to debrief and become their snitches.

In struggle!

Prisoner Human Rights Movement

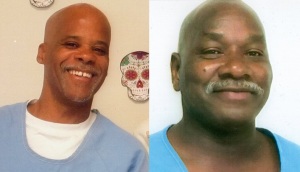

©Dec. 1, 2017, Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa and Baridi J. Williamson. Send our brothers some love and light: Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa (R.N. Dewberry), C-35671, and Baridi J. Williamson, D-34288, SVSP C-118, P.O. Box 1050, Soledad CA 92960.

[i] See “CDCR Task Force Report on Gangs, Violence and SHU,” 1986, citing CDCr’s 1971 “Report to Gov. Ronald Reagan on Revolutionary Organizations”

[ii] Same as above

[iii] See “Melancholy History of Soledad Prison,” by Min Yee

[iv] See case of W.L.Nolen, et al. vs. Fritzgerald, Warden of Soledad Prison (1969)

[v] See Madrid v. Gomez (U.S. Dist. Ct., N.D.Cal., no. c-90-3094), 889 F.Supp. 1146 (1995)

[vi] See Madrid, above, at footnote 5

[vii] See article, “Potty Watch: PBSP Human Rights Violations” by the Freedom & Justice Project, published in Prison Focus April 2011

[viii] See Madrid

[ix] See PBSP SHU prisoners’ letters and interviews, Pelican Bay Information Project (PBIP)

[x] See 2017 Stanford University lab report by the Human Rights in Trauma Mental Health Lab, detailing the ongoing negative health consequences Ashker class members have suffered following their release from long-term solitary confinement into the general prison population.

[xi] Ashker v. Brown, class action (U.S.N.D.Cal. no. 09-cv-05796-CW) settlement 2015

[xii] Walker, Taylor, “Two Years After End of Indefinite Solitary in CA, CDCR Violating Terms Of Settlement, and Inmates Experiencing Lasting Psychological Effects, Says Center For Constitutional Rights,” 11/22/17, WitnessLA, witnessla.com

[xiii] See Brown v. Oregon Dept. of Corrections, 751 F.3d 983, 988 (9th Cir. 2014)

You must be logged in to post a comment.